A Rough Start

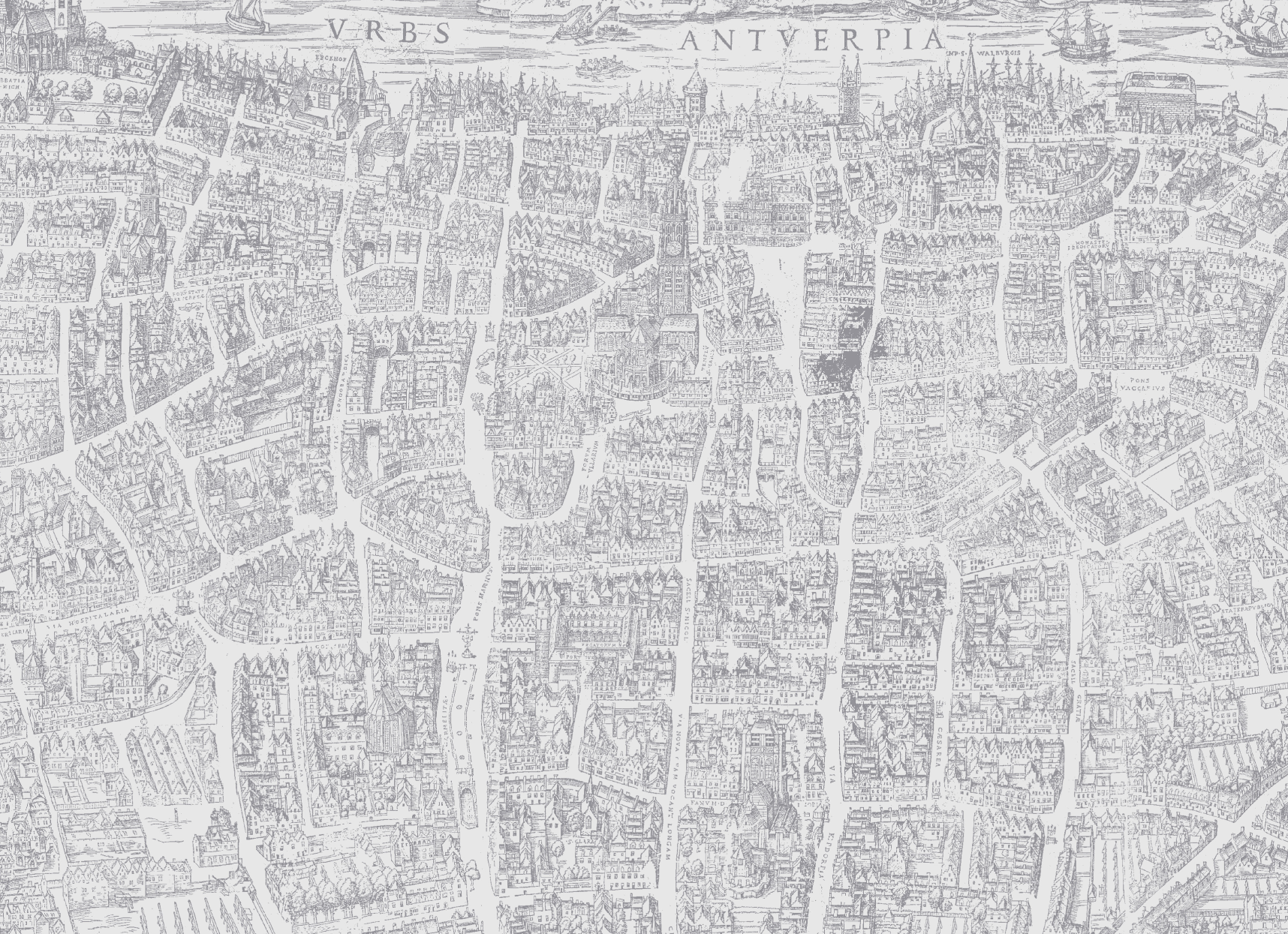

In the middle of the 16th century, Antwerp was a city of opportunity, its port buzzing with merchants, scholars, and artisans. Among them was a young Frenchman named Christophe Plantin, newly arrived with his family and a head full of ambition.

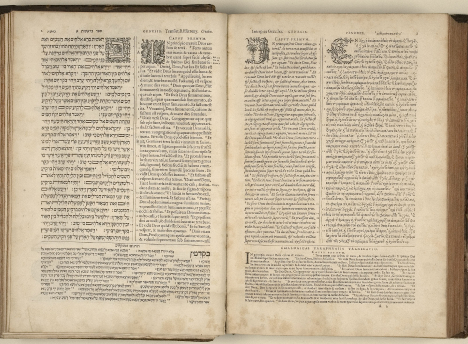

Plantin was a bookbinder by trade, known for his meticulous craftsmanship and skill with leather. He had made a name for himself creating ornate, hand-stitched cassettes for the nobility, and even caught the attention of Gabriel de Zayas, the secretary to King Philip II of Spain.

But in 1555, fate struck as sharply as the blade of an attacker's sword. One evening, as Plantin walked through the streets of Antwerp carrying a leather case destined for the Spanish king, he was ambushed by drunken men. In the chaos, his shoulder was pierced by an attacker's blade, leaving him unable to continue the physically demanding work of bookbinding.

For many, such a blow would have been the end of their career. But Plantin saw it as a chance to reinvent himself. With the help of Hendrik Niclaes, a wealthy merchant and leader of an Anabaptist sect, Plantin purchased a printing press and began a new chapter. His first book rolled off the press in 1555, a modest but well-received work titled “Institution d'une fille de noble”, a guide to educating noble girls. It was the beginning of a journey that would transform him from a skilled artisan into a titan of the printing world.

(Photograph of metal type pieces)

Explore Antwerp in the 16th century to learn more...